DIGITALITY OF THE OPERA - TWO CASES

Jelena Novak  "The term 'digital art' has itself become an umbrella for such a broad range of artistic works and practices that it does not describe one unified set of aesthetics". [1] Computer art and multimedia art are two terms that preceded the term digital art. Similar is with the world of opera, the term 'multimedia opera' was used by the authors who integrate digital technology to their operatic opus, and the term digital opera is less often used (for example "digital opera in three dimensions" Monsters of Grace by Philip Glass and Robert Wilson). Generally, it seems possible to distinct two broad groups of digital opera: first includes works whose digitalism is primarily based on usage of multimedia means, and second, includes much lesser scope of works whose whole structure is built on digital principles. In this text I will demonstrate those two groups of operas on two examples - 'multimedia opera' Itinerario do Sal (2005) by Portuguese poet and composer Miguel Azguime and opera One (2003) by Dutch composer Michel van der Aa. "The term 'digital art' has itself become an umbrella for such a broad range of artistic works and practices that it does not describe one unified set of aesthetics". [1] Computer art and multimedia art are two terms that preceded the term digital art. Similar is with the world of opera, the term 'multimedia opera' was used by the authors who integrate digital technology to their operatic opus, and the term digital opera is less often used (for example "digital opera in three dimensions" Monsters of Grace by Philip Glass and Robert Wilson). Generally, it seems possible to distinct two broad groups of digital opera: first includes works whose digitalism is primarily based on usage of multimedia means, and second, includes much lesser scope of works whose whole structure is built on digital principles. In this text I will demonstrate those two groups of operas on two examples - 'multimedia opera' Itinerario do Sal (2005) by Portuguese poet and composer Miguel Azguime and opera One (2003) by Dutch composer Michel van der Aa.

While writing The Death of the Author ("La mort de l' auteur", 1968), Roland Barthes contemplated on hand which moves relentlessly, on mixture of different texts, on performativity of the body which writes. This highly influential essay still conceptually coincides with different contemporary artistic practices. In recent sound poetry performance work The Air of the Text Operates the Form of the Inner Sound ( O Ar do Texto Opera a Forma do Som Interior ) by Miguel Azguime (1960), Barthes's text was metaphorically played on the stage. Dressed like a cabaret man in dark elegant shirt, dark pants with braces, Azguime himself was sitting at a table, talking in Portuguese, writing, laughing and making percussive noise. His narrative was on authorship, sounds, silence, gaze, body, text, the air. He was making sounds by pencil as he simulated the act of writing. Those percussive sounds together with the sound of the verses he recited were processed live with electronics. Narrative on problematization of the authorship together with the gestures of the author/performer/writer served both as a dramaturgical frame and sound material. [2] After experiencing it, you will probably ask yourself about its genre: Is it an electro acoustic music composition? Is it a sound poetry? A music-theatre, performance art, a multimedia opera? Or, it is all of those together? The Air of the Text Operates the Form of the Inner Sound presents one of the strongest Azguime's interests - to show that the art worlds are movable, interconnected and approachable to different deconstruction procedures. Walking beyond the boundaries of major, established disciplines is one of the significant features of Azguime's poetics. He is the author of the verses; he recites them and also performs the music composed of rhythmical proliferations of sounds, words and gestures. Azguime's different artistic activities finally are together in an institution which could be called theoretical performance. It looks like a theatre, but it is not. Author or just the signifier of the author shows the consciousness both of performativity of theory and theatricality of performance. His theoretical approach is structured as poetry: "To unveil the mystery of the author's absence

To shed some light over the question

A question lies asleep without an answer

The author does not sleep but he is absent

His presence is absent

Therefore the question remains

Whilst his absence lasts

The presence questions itself

In the silence of the presence of the absent author

The solution enquires itself regarding this question

The question is without words

The question silences sound

The sound licenses the question

It is a question of silence minus the author" [3] Although the meaning of the text reveals theoretical occupation by problems of the authorship, the performativity of text shows Azguime asking him/us one simple question: Where the boundaries of music are? While doing so, Barthes-like theoretical story on music becomes the music itself, and that is the most fascinating symbolic effect of the whole piece. Post-Cageian set of enjoyments and frustrations gathered over the statement Everything I do is Music , reappeared in their post-technological form. Every time this hyper-textual piece for a speaking percussionist and live-electronics is performed, the author has been reconstituted live, together with the whole institution of music.

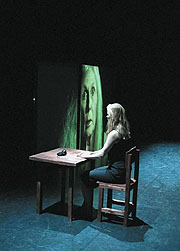

Photo: Miguel Azguime, Itinerario do Sal Text Operates the Form of the Inner Sound became the part of the multimedia opera Itinerario do Sal by the same author. Digital technology is extensively used both in visual and audio layers of the opera. Digital means primarily multiply the layers of projected texts on stage, and make them more virtuaous, and more movamble. Same happens with the sound - Azguime's voice, and the text he performs on stage became multi-semantic, and multi-sonoric due to the electronic processing of the performed sound situations. One the other hand, opera One is based on digital principles of structuring [4] that promotes 'prostheticism' as the main structural effect of the piece. Michel van der Aa strongly problematizes prosthetic relations in his piece Here (In Circles) (2002) and opera One (2003). Singer Barbara Hannigan is one and only diva of this opera/performance relation. Van der Aa is a triple auhor of the piece - he composed music, directed video and wrote a libretto. [5] Opera starts in complete dark. There are two white sheets on the stage. Behind one of them is Barbara Hannigan who rhythmically repeats one tone. First she sings 'alone', and when electronics starts, it takes exactly the same tone from the soloist and continues to reproduce it in its superior technical durability. There is the author's first reference on the notions of one, only, unique. In today's world of explosion of the information which is cloning and replicating its own realities, the notion of one, only, unique is out of trend. Van der Aa counts exactly with that problem. , describes him. Composition by the same author Here (In the Circles) could be considered as a study for the examined opera. Moved by the rhythm of living in media and information society, he is founding the dramaturgy of the piece in the constant aceleration of the music flow. There is the playing with the fast forward rewinding sound, and also counterpointing the live performance to fragments recorded at the very same concert and broadcasted during live playing. With all above mentioned 'techniques' van der Aa also plays in context of the opera. One become multiple in many ways: Barbara Hannigan meets her own reproduced video image on the stage. They are both dressed in the same way, they are both of the same size, and they both have the same voice which is the most important thing for the whole opera. Multiplying of her own representation was a great virtuoso task for Hannigan, both visually and auditively.

Photo: Michel van der Aa, One This opera ends with meeting of real Barbara Hannigan and her representation who is simulated to be around fifty years older. Two flows of time ended up together. Virtuous usage of technology in this work, and also mechanical, almost hysterical, virtuosity are deeply integrated in the opera tissue. That 'natural' integration is the strongest actuality of the piece.

Comparation of the poetics and structure of Azguime's and van der Aa's operas shows different procedures, and different usage of multimedia and digital means. These two pieces stand on opposite sides of what could be called 'digital opera'. While Azguime explores the virtuos boundaries of multiplication of layers of the piece, richly extended by the digital technologies, van der Aa shows how it is possible to simulate digital way of thinking in the operatic world. Symptomatically distant, those two pieces show the extended field of possibilities for thinking the digitality of the opera today.

[1] Christiane Paul, Digital Art , London , Thames and Hudson , 2003, p. 7. [2] For this occasion I used the fragments of my text Percussive Silence of Words that was written for the Portuguese Music Information Center . See: www.mic.pt [3] Quotation from: Miguel Azguime, Prologue: the Oracle or the Passage, in: The Air of the Text Operates the Form of the Inner Sound . [4] Basic principle of the analogous presentation of data is continuity, and digital presentation of data is consisted of the values measured in discrete intervals. [5] In this text I use fragments of my text Prosthetic Music, Michel van der Aa's Case. See: http://www.doublea.net/articles/a_novak.html

|